Practical Rateless IBLT: Part 1

This is a two-part blogpost presenting a friendly digest of the PRIBLT paper and some unsolicited life advice. Part 1 sets up the problem of set reconciliation and explores prior art. Part 2 plunges into PRIBLT.

The problem

By convention, we turn to Alice and Bob to define the problem. What trouble are they up to this time?

Here’s the deal. Alice has a bag of things. Bob has a bag of things. Alice and Bob are 100 miles apart and communicate only by phone calls. How would they efficiently figure out the symmetric difference between their bags: the things that either Alice has but Bob doesn’t, or Bob has but Alice doesn’t?

In other words, Alice and Bob wish to reconcile their sets of things. Such is a problem of set reconciliation in distributed systems.

Set reconciliation

To quantify things, we assume a speech rate of 2 words per second.

“I’ll just say out loud everything in my bag, so you can figure out the difference on your side!” Bob took the lazy road.

This obviously works, but what happens when there are thousands of things in their bags each? Let’s say 1000 each. It’ll take Bob more than 8 minutes to utter them over the phone line.

Can they do better?

Probabilistic data structure

Instead of enumerating everything in his bag, Bob can send over a Bloom filter, calculated from his bag, for Alice to rummage through. Apparently, Alice and Bob would have had training at MIT + CIA to understand how to do this, so we further assume they have such experiences.

In fact, Alice and Bob are quite a clever duo. Instead of Bloom-filtering their entire bags, they first organize the contents of their bags into Merkle tries. They reconcile their tries using Bloom filters starting from the top and only dive into sub-tries when needed.

However, the communication cost of this approach is at the order of:

\[O(log|A| + log|B|)\]where \(A\) and \(B\) refer to Alice and Bob’s bags respectively, and the absolute value operator measures the size of a bag.

This approach is an interactive process involving a lot of waiting and responding. They don’t like it. Sometimes, their bags are 99.9% the same. But their phone bill still depends on the size of their bags.

Coding theory

Alice and Bob recall their training at CIA and decide to put their coding skills into practice. Specifically, they use Invertible Bloom Lookup Table (IBLT) for encoding and decoding.

Here’s how the IBLT encoding works. Take a bag of \(n\) things. We want to produce a total of \(m\) codes from them. The way we do that is to map each of the \(n\) things into \(k\) codes, \(k < m\). For example, Alice might say, “okay, this thing is mapped to the 3rd, 17th, 29th, and 41st of my 250 codes.”

The value of a code is computed from the things mapped to it, which involves XORing (\(\oplus\)) the things together as well as XORing their hashes together. We call the former \(sum\) and the latter \(checksum\). A code is the tuple \((sum, checksum)\). The only thing we need to remember about XOR is that a thing XORing itself yields 0, or \(x \oplus x = 0\).

Alice encodes the content of her bag into \(m\) codes, and sends these codes to Bob. Refer to these codes as \(IBLT(A)\). Bob also encodes the content of his bag into \(m\) codes. Refer to these codes as \(IBLT(B)\). Now Bob can start to figure out the set difference, denoted as \(A \triangle B\). The central thing about IBLT is that:

\[IBLT(A) \oplus IBLT(B) = IBLT(A \triangle B)\]This means with Alice’s codes available, Bob could just XOR them with his own codes in a pair-wise zipping fashion, and decode (i.e. \(IBLT^{-1}\)) the zipped codes. The result of this decoding is, tada, the difference between \(A\) and \(B\). But how does decoding work?

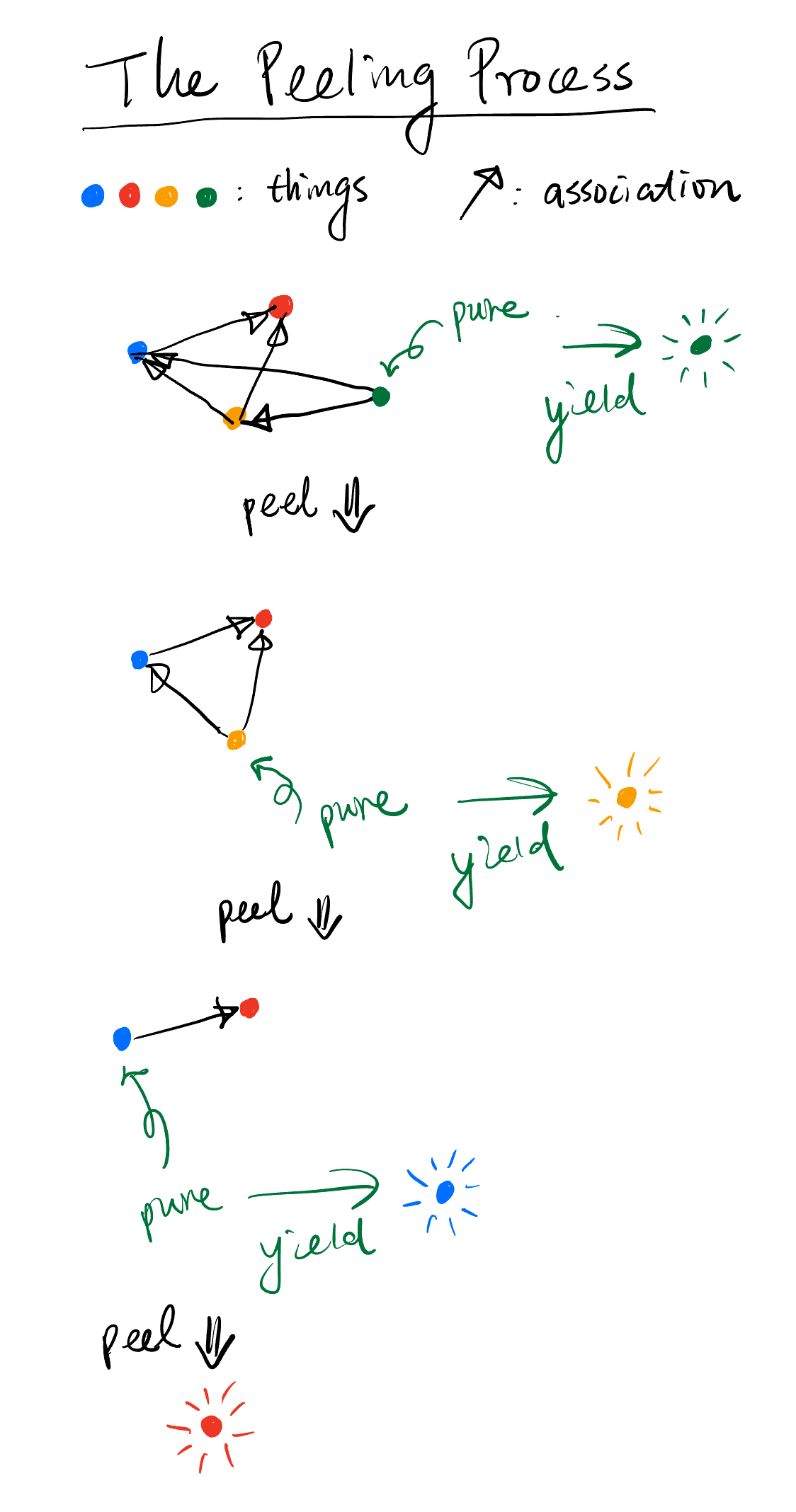

Peeling

Decoding a set of IBLT codes resembles a peeling process. The idea is that among these codes, there exists at least one pure code (otherwise decoding would fail and this IBLT is no bueno). A pure code is a code where its \(checksum\) equals the hash of its \(sum\), which basically means \(sum\) is already a decoded value, our lucky guy.

We run this lucky guy over the IBLT’s mapping function to find out the other codes this guy also maps to, and peel this guy off from those codes by XORing this guy into them (remember, \(x \oplus x = 0\)).

We repeat this peeling procedure until there are no pure symbols left. The guys we peeled off from the codes are the prizes - the set difference (\(A \triangle B\)).

IBLT is non-interactive! It means there’s minimal waiting involved. Alice sends her codes to Bob in one go and hangs up the phone. Bob takes it to the finishing line on his own.

Excursion: learning a new field

The IBLT peeling procedure resembles the process of learning. It is quite a revelation.

The ideas of a field are often associated with one another. Their meanings are defined by their associations. Remember the dizzying feeling when you plung into a new field where the terms all sound super foreign, and their definitions all seem to cross-reference in a cryptic way? That’s totally normal.

Think of those ideas as IBLT codes. They are raw new ideas for you, only in encoded form. The key is to find pure codes, or ideas that you already understand (if you understand something, you can TL;DR it without breaking a sweat). Peel the IBLT from there.

A common mistake is to equate understanding as remembering the associations. That’s just memorization.

Next we return to a critical problem of IBLT.

🐔 & 🥚

The problem is deciding \(m\), the number of codes needed. Choosing an \(m\) too small, decoding might fail because the codes are too few to contain the information of the set difference. Choosing an \(m\) too big, Alice gets a dry mouth uttering all the codes over the phone. We obviously wish to choose the smallest possible \(m\) but not smaller.

Denote the size of the set difference as \(d\). The smallest permissible \(m\) depends on \(d\) – it just makes sense from an information-theoretic standpoint. But here lies a chicken-and-egg: we perform set reconciliation because we wish to know the set difference, but in order to do so we need to pick \(m\) which requires knowing \(d\), the size of set difference!? It becomes a guessing game. Guess it wrong, we use an \(m\) too small, decoding fails, and we have to bump up \(m\) and do it again. This is not ideal.

Making it rateless and practical

PRIBLT = IBLT made Rateless and Practically so.

The big ideas are:

- Instead of picking an \(m\), we let the IBLT produce a continuous stream of codes. You take as many codes as you need to succeed at decoding. This is the rateless part.

- The number of codes needed for successful decoding is on average a small constant multiple over \(d\). Furthermore, it still takes constant time to perform the IBLT mapping procedure. This is the practical part.

In other words, Alice and Bob play no guessing game. Alice utters codes into the phone until Bob tells her to stop. On average Alice utters between \(1.35d\) and \(1.72d\) codes into the phone when Bob stops her, even when they have millions or more things in their bags. No dry mouth, and guaranteed success of decoding. The approach is nothing short of magic.

Part 2 elaborates on how PRIBLT works.